Books I have enjoyed in 2022

Here are the books which I have finished this year and would also recommend.

Last year's reading slump continued into this year. But I'm in a new place with a nice library and a couple of great bookstores and have also added many of the books that were waiting for me in storage to my TBR shelf. Also, I discovered that I needed reading glasses and... while I'm not over the blow to my ego, it has made a huge difference. What I thought was a lack of focus was actually a lack of ability to focus.

The English Understand Wool

Marguerite, a reserved, sneakily precocious 17-year-old raised by an impossibly privileged and comically exacting mother, endures a traumatic family revelation and navigates the notoriety it brings in this lovely novella. The overriding principal Margeurite’s mother has imparted to her is the avoidance, at all costs, mauvais ton (“bad taste”). But how do you live up to this dictum when the sullied tide of this fallen world washes away everything you thought you had and knew?

How lucky do I feel to have noticed, moments before plopping my haul on the counter at Phinney Books, the that the handsome display of books next to the cash-wrap was from New Directions? Insanely. The lineup of authors they have chosen to start a new series (Storybook ND is preposterously stacked. The English Understand Wool grabbed me first of byline: Helen DeWitt is a writer whose work comes about as close to my idea perfection as anybody doing it right now. And this effort? Just one delectable morsel of a chapter after another until you’ve consumed an unassailable masterpiece in a single sitting.

This satirical character study reads like the wordly, eccentric tales which Wes Anderson movies can only gesture towards. It is an absolute joy for any fan of DeWitt and an ideal introduction to the unititiated: funny, short, and devilishly clever. Now, is it mauvais ton to wonder whether $18 is too much to pay for what is effectively a short story in a cloth binding? All I can say is that the Irish know linen, the English understand wool, and New Directions understands the written word.

Gold

From the bulging file of things I was wrong about: I once was convinced that the cover design for the New York Review Classics books is boring and somewhat crude. It may be a response conditioned by encountering so much joy inside those covers in the meantime, but whenever I see one of these treasures faced out, I shake my head at my old self. What perfect harmony between image The cover of this new Rumi translation seemed quite honestly seemed to glow as it drew me across the library to pull it off the shelf. The startling, electric words I found within cemented the enchantment. Here are verses brimming with the particular clarity of intoxication, perfectly contemporaneous while 800 years old, and not at all how I remembered the experience of reading Rumi. In Persian-American poet and singer Haleh Liza Gafori's brilliant translation, these lyrical selections awaken and lodge themselves in my consciousness. This book is an absolute gem. "Meet us in the land of insight / Camped under ecstasy's flag".

The Final Forest

Big Trees, Forks, and the Pacific Northwest

I regret how many times I looked at The Final Forest sitting on the shelf and thought I could hold off on another book about trees. This book is decidedly about people and the evolving ideas about and conflicting attitudes towards humans' relationship to the natural world, and it knocked my boots off. To contextualize the context of the effect of efforts to protect old-growth forests on the exemplary community devoted to logging them, the town of Forks, Washington, William Dietrich allows gives voice to so many actual peoples' voices the seemingly polarized political debate becomes a patchwork of real human experience. An incredible document, this helped me understand the stakes and the contours of the changing pacific northwest, and the Olympic Peninsula in particular

The House in the Cerulean Sea

I needed something quick that would feel good to read, and TJ Kulne's YA Fantasy tale of a mysterious oprhanage and a by-the-book child welfare case worker more than fit the bill. Here is a book his is a book about finding a home and what it means to find (as opposed to merely have) a family. The prose wasn't always as magical as the subject matter, but the characters were good and the love story was very sweet. Felt good, man.

A Tidal Oddyssey

Ed Ricketts and the Making of Between Pacific Tides

As I began trying to wrap my head around the crazy, new-to-me world of tide pools on the coasts of the Olympic Peninsula, a book that kept coming up in every list and bibliography was Between Pacific Tides by Edward F. Rickets and Jack Calvin. This isn't that book. But while I was still waiting for it to be available at the library when I saw a post by the Well-read Naturalist about this book, an account of how that groundbreaking work on Pacific marine ecology came into being.

Now, a book about a book isn't necessarily the sexiest thing. But this guy Ricketts was an incredibly interesting fellow: he was the inspiration for the protagonists of two books by John Steinbeck (and a collaborator with the legendary Californian Nobel laureate as well), a garrulous renaissance man who changed the course of a scientific specialty from outside the confines of academia and a deep thinker/talker/listener who fostered an atmosphere of curiosity and discussion which influenced a bunch of interesting people hanging around his lab, people like Jospeh Campbell, Henry Miller, John Cage.

Between Pacific Tides is a striking blend of art and science communication which has influenced generations. It is amazing. Its key insight is that the interrelatedness of the members of actual ecological communities, rather than taxonomic organization, can be the starting point for understanding life, has had incredible influence, to the point where it now seems like a given. The story of this work's long journey is as interesting as the genealogy of its ideas, as Rickets' persistence in the face of academic skepticism and publishers' skepticism triumphs in the end. What an interesting story about an interesting human.

Second Nature: A Gardener's Education

A Gardener's Education

Before he became the tribune of a renewed psychedelic era, before he promulgated a perspective on the food system we live in that changed everything, Michael Pollan brought his cerebral and affably discursive style to bear on the subject of gardening. As I try to go from a novice gardener to the caretaking of a small plot of land, I enjoyed this account of his own journey. Pollan's writing is lucid and his thoughts informed by wide reading and reflection on the subject. It was his recounting of a battle with a woodchuck, read as an excerpt on a podcast, that led me to pick this up. I'm glad I did.

Orwell's Roses: A Memoir

I honestly didn't want to read a book about Orwell. But never doubt Rebecca Solnit: clearly written, incisive, insightful and gifted at bringing all kinds of unexpected connections to bear on a subject. Her aim is to tease out how Orwell's lifelong interest in plants and gardening inform a more complete understanding of him as a writer and thinker while exploring the role of pleasure in art and politics.

[T]he least political art may give us something that lets us plunge into politics, that human beings need reinforcement and refuge, that pleasure does not necessarily seduce us from the tasks at hand but can fortify us. The pleasure that is beauty, the beauty that is meaning, order, calm. Orwell found this refuge in natural and domestic spaces, and he repaired to them often and emerged from them often to go to war on lies, delusions, cruelties and follies...

I finished Orwell's Roses and would have enjoyed immediately turning back to page one and reading the book again if it hadn’t planted and nourished half a dozen other appetites to be pursued elsewhere.

Night Soldiers

A Novel

I don't often read spy thrillers, but every so often someone recommends a book to me and I wonder why that is. in Night Soldiers, Furst creates an intoxicating atmosphere, deftly evoking the romance of pre-war Paris and the incomprehensible suffering of the Eastern front, portraying the high-stakes backdrop of war itself, charting the machinations at dark forces manipulating resistance battles for their own gain, and detailing the terrifying competence of spies practicing their craft. But with atmosphere so thick, sometimes things got a bit suffocating, and the pace was bogged down from time to time. The novel's strengths more than made up for those lapses. Night Soldiers uses the life of one Bulgarian boy recruited to the Soviet intelligence service to anchor the larger struggle of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia for Europe from 1934–45. It must have taken an extraordinary amount of research to create so much convincing specificity while retaining the sweep of an epic narrative. This is a very top shelf spy novel.

Elwha

A River Reborn

In 2011, a Montana contractor removed the first pieces from two concrete dams on the Elwha River which cuts through the Olympic range. It was the beginning of the largest dam removal project ever undertaken in North America--one dam was 200 feet tall--and the start of an unprecedented attempt to restore an entire ecosystem. More than 70 miles of the Elwha and its tributaries course from the mountain headwaters to clamming beaches on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Through interviews, field work, archival and historical research, and photojournalism, The Seattle Times has explored and reported on the dam removal, the Elwha ecosystem, its industrialization, and now its renewal. Elwha: A River Reborn is based on these features. Richly illustrated with stunning photographs, as well as historic images, graphics, and a map, Elwha tells the interwoven stories of this region. (Publisher's Description)

When I Sing, Mountains Dance

A Novel

Have you ever wondered what would happen if Haruki Murakami had tried to create his version of Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County, but in remote Catalonia, with naive but poetic language and (perhaps ironically because we're talking about Catalonia) less surrealism and more folklore? And in under 200 pages?

When I Sing, Mountains Dance is a polyphonic novel whose specificity of place pervades it with extraordinary depth. That place is a small town in the Pyrenees, where the physical and spiritual relics of generational tragedy (civil war) litter the landscape, and a particular family is scratching out a life as natural catastrophe and personal trauma sometimes overtake things. The totality of the place seems to be telling this story. Entries in this collection of monologues are voiced by: clouds, ghosts, mushrooms, deer, witches, mountains, and homo sapiens. The kaleidoscope of perspectives is playful while also grounding the events to an almost elemental perspective. "Here," says a whole, peopled landscape, "is life; it isn't always easy, but it is very much life."

Irene Solà's 2019 novel was translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem and published by Graywolf Press this year. I ate up its 18 short chapters like so many exquisite little tapas. I don't mean that in an insulting way. Consuming tapas and short chapters of adventurous literary fiction are literally two of my favorite things. Plus this book also let me enjoy remembering the only time I have ever been in the remote Pyrenees, visiting a friend for a week a loooooong time ago. How we took a walk that ended in an improbable ruin perched in a place where nobody should be building anything, were overtaken in a microscopic town by a herd of demonstrative sheep, lost power in the middle of one freezing night in what was still mostly a barn, cobbled together dinners from the neglected pantry of poets and painters, and in general enjoyed feeling alive in majestically unpeopled spaces. That setting felt quiet while also crackling with a capability, if given full attention, of saying more than I was quite ready to understand. And it is surely my own memory playing tricks on me, but... this novel? It felt like that.

The Last Wilderness

A History of the Olympic Peninsula

Every geographically-unque region should be so lucky as to have someone like Murray Morgan to capture it forever in prose. The Last Wilderness is so evocative, hilarious, informative and I can't imagine it ever losing its place as the definitive introduction to the Olympic Peninsula. Researched with obvious care and undoubtedly benifits from conversations with old sourdoughs and lifers of all stripes from a place that he clearly loved. There are stories of the first peoples here and some forays into the natural wonders of this jungle of giant firs and cedars, glaciar-clad mountains towering straight up from the sea, and rivers teeming with salmon, but this is first and foremost an acount of the loggers and prospectos, the confidence men and utopian cultists, the wobblies and conservationists and all the other colorful characters that have peopled this wildest corner of the conttinental U.S.

This is one of the books I've gotten at Port Book and News in Port Angeles to help acquaint myself with the Olympic Peninsula and I read through it a second time to whet my appetite for the place before moving here. I loved its first sentence so much, I suggested ot to Madison Books for the "First Lines that Last" feature in their newsletter last year.

The Dawn of Everything

A New History of Humanity

Understanding that we have the power to make this world better is especially important during times when everything seems aligned to thwart us. Among the most profound obstacles to imagining a world without exploitation and oppression is the received wisdom telling us that it has to be this way. That it has always been this way, or on a linear progression to being this way. In The Dawn of Everything, archaeologist David Wengrow and the late anthropoligist David Graeber have given us a sprawling, challenging and inspiring corrective to some of the most entrenched furrows of that received wisdom.

One of their principal targets is the idea that the adoptioan of agriculture necessarily meant a wealth accumulation, inequality and technological acceleration. This account has been popular in some bestselling books of recent years (such as Guns, Germs and Steel, Sapiens, and Against the Grain) but ignores the growing body of evidence against it.

The idea that we have passed through a "progression" of development from hunter-gatherers to sedentary agriculturalists to urban city states to a globalized web of capitalist nation states is itself one of the enlightenment era just-so stories that don't stand up to scrutiny, at least according to Graeber and Wengrow's survey of recent research. People have lived in all sorts of ways, sometimes in very large numbers and in arrangements that lasted for hundreds or thousands of years. Things, it turns out, are far messier and perhaps more hopeful than we've been led to believe. Anyone who enjoyed Debt: the first 5,000 Years or any of the much-beloved Graeber's work won't need any arm-twisting. This is provocative, captivating and mostly convincing extrapolation of one of Graeber's oft-quoted lines~:~ "The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently."

The Dry Heart

It may not be possible to start The Dry Heart and not finish the book before closing it. It is as if this intimate, unsparing account of a marriage's unraveling gets right under your skin and there's nothing to do about it but to keep reading as if scratching a phantom itch. The clarity and directness of its prose feels at first like an unbearably and intensely focused light... it reveals all, like a the lamp of an operating room. Another metaphor, from the title, is even better: this text is dry and desiccated in a breathtakingly clarifying way. What a title. What a first line.

Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet

You don’t see a lot of self help books on your average “Global Climate Change” reading list, unless you count those helping people attend to their energy use or consumer habits. This one is different.

In Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet, Nhat Hanh (or Thay, as he was known), patiently guides us to take care of ourselves in order to foster our resiliance and streng for the work of taking care of eachother and the world. When it sometimes feels like we face challenges so overwhelming that there is nothing we can do to help, Thay offers wisdom to put that in perspective. I will not soon forget his account of using meditation to overcome despair when working to stop the war in his native Vietnam, another overwhelming, life-threatening and seemingly intractable challenge.

There is great teaching here on listening compassionately to others whom you may be inclined to fear or hate. This book offered me new tools to keep my cool and seek genuine dialog when talking to people I might see as complicit in the climate crisis or whose reluctance to face it I may resent.

The idea that surviving global climate change means first dealing with our own anxiety and despair seems both obvious and under-appreciated. My intuition is this book will be most impactful for those already predisposed to buddhist teachings, but Thay’s accounts of political engagement and the interconnectedness of everything . The author of 75 books available in English (his 1992 work Peace Is Every Step is particularly resonant to me), Thay died just days before I am writing this. His legacy is enormous and this book is one epic and generous gift before departing.

Tree

A Life Story

How about a book that feels like sitting down with under a tree with renowned envirobmentalist David Suzuki, as he gives a magesterial, stem-winding biography of it. Yes, a biography of a tree. Or perhaps it's a botanograpy? Anyway, I throoughly enjoyed a masterful teacher skilfully sliding from topic to topic in a supernaturally informed lecture which somehow never feels exhaustive in the manner of a textbook.

I am, admittedly, very into trees. Anyone else here will find startling facts, pleasing reveries and memorable anecdotes. Somehow he covers the implications of the similarity of hemoglobin to chlorophyll, the life of a galapogos tomato whose seeds can only germinate if they pass through the digestive system of a tortoise, and many more tangents through lichens and salmon, sunlight and spotted owls, but it is all, satisfyingly, in the service of the story of a single tree from the instant the seed is released from a cone until, hundreds of years later, it lives on as a nurse log on the forest floor, fostering the life of a future generation.

The Living Mountain

A Celebration of the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland

"My eyes were in my feet." --Nan Shepherd

The beautiful, patient specifiity of Nan Shepherd's meditation on years of wandering the austere Cairngorm mountains in Scotland works on you like a spell, its prose worn over like the stones of a weatherbean plateau sat. The Living Mountain sat unpublished in a drawer for 40 years and then spent 40 more building its reputation as a classic of nature writing. As Robert Macfarlane says in his introduction to this edition: "Most works of mountain literature are written by men, and most of them focus on the goal of the summit. Nan Shepherd's aimless, sensual exploration of the Cairngorms is bracingly different."

Pure Colour

A Novel

If you would like to read something unlike anything you have ever read, Pure Color is an excellent choice. Your expectations are likely to be confounded, even if they derive from Heti's earlier works, as this isn't the high-wire act of self-scrutiny that made How Should a Person Be and Motherhood so celebrated. Whether you will like what you find is harder to say, but I certainly did.

From one of its brief chapters to the next, his book can feel like a modern-day fable, like an autofictional foray into magical realism, or like a transparent vehicle for smuggling philosophy and aesthetics into the Fiction section. Mostly, though, it feels like having a conversation with someone you slowly realize is an absolute kook. This is a good thing! It's the kooks who end up with all the out-there ideas that start our movements, change our paradigms and shake up our world views. And boy does the cosmology of protagonist Mira fit the bill. Mira is on her way to being art critic who gets hung up on an unrequited love and waylaid by the death of her father. Some of the book's dominant conceits, like that we are living in the first draft of the world during the moments where God is on the verge of ripping it up for the second, and that everyone is either a bird, a fish or a bear (a sort of faux-naive myers-briggs diagnostic for a world in which the supreme being is a sort of critic) scaffold a unique conception of the world which undergirds the story. The account of Mira's life often reads someone channeling the cosmic assurance of a lost pre-socratic philosopher into a spiritual text for children.

Heti takes weird, simultaneous stabs at the ineffable and mundane and again reaffirms herself as a writer unafraid to go into new places that surprise me and make me think. I didn't know about this book until I heard Heti talking about it on the Between the Covers Podcast (which, if you don't know about it, is just something you're going to need to really check out).

Life Among the Savages

If you, like me, have only read Jaackson's works of horror and mystery, Life Among the Savages, you are in for a treat. In this lightly fictionalized memoir of six years of raising her family, Jackson uses her storycrafting craft to depict the chaos of home life with droll self-deprecation and an outsider's eye on the quirks of small town life in New England. Resolutely from the 1950s, this feels utterly contemporary. Charming.

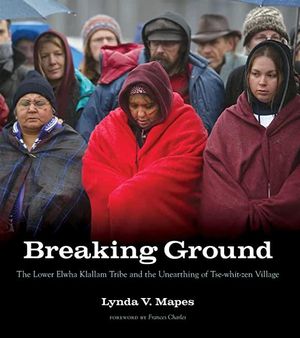

Breaking Ground

The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and the Unearthing of Tse-whit-zen Village

After I finished The Last Wilderness, I returned to Alan at Port Book and News, who had recommended it to me for learning about the Peninsula, and asked him what should be next for learning about the area around Port Angeles. Without even a second of hesitation he walked to the shelf, plucked off a copy of Breaking Ground and put it into in my hands. I am so glad he pointed me to this amazing account of a gripping local story that helped to reframe my perspective on this specific part of the world.

In 2003, routine work at the site of the largest construction projects in the state of Washington turned up the first archeological evidence of what eventually was discovered to be the largest pre-European contact village site ever excavated. Stopping work on an enormous project was controversial, but it was the story of how the memory of the site had been ignored and erased which was the most profound revelation. This story encapsulates so much about European settlers' attitudes towards native peoples' cultures, and the hurt this has caused for generations. There are hopeful notes about changing attitudes, and it is certainly noteworthy that the project with so much money and so many interested parties and agencies was indeed stopped.

This is a closely-reported story, and certainly feels definitive. Mapes clearly interviewed a lot of people and the eyewitness accounts yield interesting results, such as an incredibly thorough depiction of a burning ceremony (where a feast table, clothing and other objects were burned for the ancestors). I learned so much from this book.

Books I have enjoyed in 2022

Books I have enjoyed in 2022

Books I have enjoyed in 2022

This shelf was updated on Oct 20, 2022.

See the history of updates to this page or Access this shelf as json.